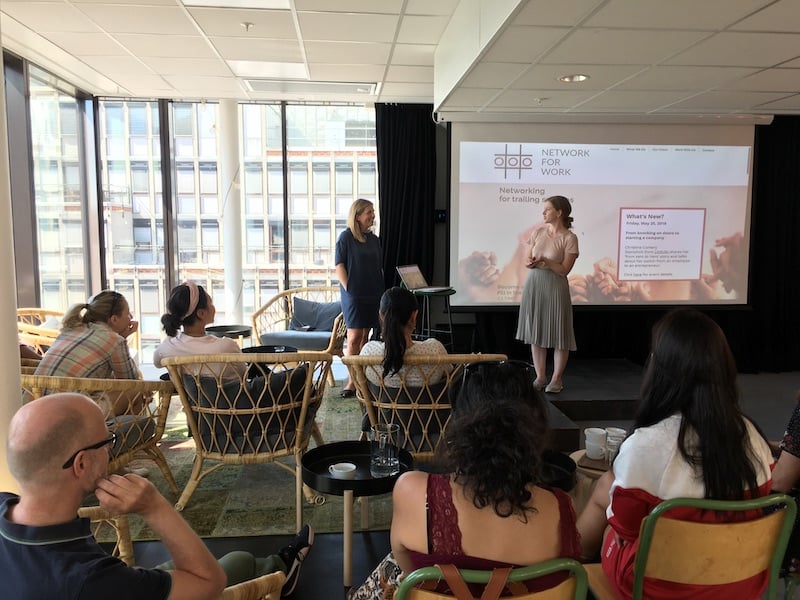

Network for Work (NFW) is an organization that has been on our radar for about a year. A little while after Diversify was established, we learned about the amazing work NFW was engaged in – as a strong advocate for employment opportunities and facilitation for skilled immigrants, with a particular interest in Trailing Spouses. Nikol Mard, the Founder of NFW, is a native of Czech Republic and a social scientist with a background in sociology and gender studies (undergraduate – sociology & media studies; graduate – gender studies). Like many others in Norway, she arrived as a trailing spouse and optimistic about her possibilities to secure work and settle into the society. But reality had a different path for her. Again, like many of us, she found it nearly impossible to secure work and find her ground in her new home, in this regard – her prior professional experiences and academic achievements seemingly rendered useless. After 5 years of applying to over 200 jobs and garnering herself a Norwegian (2-year long) masters level degree, she secured 1 interview. She did not get the job. Soon thereafter, she established NFW as a means to bridge the gap she experienced and one that continues to exist in Norway. Nikol does not mince words on how difficult it has been to achieve NFW’s mandate, but she remains relentless in her pursuit.

We chose to profile Nikol and her work because she is a prime example of breaking down a wall where there are no doors or windows. In spite of the challenges she faced in Norway, and having to rebuild her professional life from scratch with little help from the system, her experience was not lost on her. She did not allow self-pity, entitlement or resentment get in the way of making a much-needed difference in a barren space. She knew she was not alone in her struggle and for this reason, she created the organization (NFW) she wished was available to her when she newly arrived in Norway. By championing the cause, she became the change she wanted to see in her world. Nikol is exemplary in her endeavors, in investing her (mostly financially uncompensated) time and efforts where her and many others professional needs are unmet.

She does not merely talk the talk, she also walks, breathes, lives and sweats for the talk.

She is passionate about the cause, and speaks confidently and directly of things that should be changed. When she is not fighting the good fight for diversity and inclusion in the Norwegian professional spaces and community, or working on other entrepreneurial projects in which she is involved, Nikol is a mother of a young child and easily retains a gorgeous air of warmth around her, her presence is settling and her laugh is contagious. We find Nikol’s story and her work at NFW absolutely inspiring.

Below, Nikol tells her story.

“How would you say diversity and inclusion manifests in the Norwegian society and workplace?“

Norway has a long history of fighting for gender equality and they have come quite far. It’s no wonder then gender equality remains the main focus of diversity efforts and, from my experience, for a lot of people diversity equals increased number of women, be it in boardrooms, political parties, government, or just workplace in general. In a country that historically did not have to deal with inequality along other axes such as ethnicity (yes, I know about the Sami people but their struggle for equality is relatively recent and doesn’t go as far back as women’s rights movement), it is understandable that equal representation of men and women is the cause that most of the population can identify with. But since the 1960’s and the work immigration brought about by the oil boom, there’s another variable to look at – a person’s nationality or country of origin.

The Norwegian society has become more and more diverse but purely from a mathematical point of view – the amount of people with non-Norwegian background has increased. The changes in Norway’s immigration policy over the years influenced the type of people coming to Norway: from work immigrants of the 60’s and 70’s to family reunification and refugees of the 80’s and 90’s, and once more, the influx of work immigrants after the Eastern European countries joined the EU in 2004 and 2007.

But this increased number of people with non-Norwegian background doesn’t simply create the diversity we strive for – minorities form silos – the division of Oslo to East and West serves as an example. The labour market is not only vertically, but also horizontally segregated. For instance, it’s not only about how far up the career ladder can you get if you’re a minority, but also what jobs are available to you (if any at all!).

Perhaps rather than talking about diversity as a static term we should talk about inclusion – bringing all these different voices to the table and hearing what they have to say.

We need to learn to look at differences as resources, not as dividing markers. This is of course easier said than done but that’s why initiatives such as NFW and Diversify exist.

“What drove you to establish NFW? What was your experience in Norway as a trailing spouse?“

I established NFW to create a service I wish I had when I came to Norway.

I came to Norway because my husband got a job here. Before arriving to Norway, and some time after, I heard people say how easy it would be for me to fit in because everybody speaks English and because my education and work experience would allow me to find a job easily. Nothing could have been further from the truth. After many months of futile job search, I enrolled at the university in hopes of increasing my attractiveness on the Norwegian labour market. However, upon completion of my Norwegian graduate degree, I found myself where I began. Neither my Norwegian degree nor vast social and professional network helped me secure a relevant job. Some time thereafter, I went on a parental leave (well, not exactly ‘leave’ because I didn’t have any job to take a leave from but I stayed at home with my son for one and a half years) and through a community of international mothers, I met so many brilliant, smart, capable, experienced and educated women in the same situation as me.

It began to dawn on me that the similarities in the problems we were all facing was indicative of a huge structural problem. So much wasted talent, so much unused potential! And in Norway, a country so proud of their gender equality achievement, that there was this new class of involuntary housewives was just absurd. At that point I got called to my one and only job interview in Norway – a job I was not qualified for – but I had a reference from someone in my network.

To clarify, my success rate is very low – after hundreds of applications over few years, I only got one interview!

I ended up not getting the job but it made me realise that it’s neither the ‘hard skills’ nor what you can do that matters. Instead, it’s who you know that can get you through the door. That was when the idea of Network for Work was born in 2018.

NFW started as an organisation for the so-called trailing spouses – people who came to Norway because of their partner. I don’t differentiate between internationals following their expat spouse or internationals coming to live with their Norwegian partner. For me, both these groups face similar challenges:

- A lack of job opportunities due to lack of knowledge of the local labour market

- A lack of professional network

- A lack of personal network (aka friends).

Addressing these challenges is the main goal of NFW. During the first year we discovered that it’s not only trailing spouses who face these challenges. Other highly educated and skilled internationals find themselves in a similar situation, and even Norwegians who lived abroad and return home face the challenges of missing professional network. We welcome everyone but trailing spouses remain our main target group.

“What challenges have you encountered in your work? Where do you see opportunities?“

The biggest challenge, of course, is to bring Norwegian companies to the table.

We can provide people with information and informal network, including people relevant to their field of work, but to secure an institutionalised cooperation with a Norwegian company has proved challenging. For some, increased diversity simply isn’t a priority, others are unaware of the structural obstacles that internationals face and think their struggles are due to lack of information or effort.

In spite of many reports written on the positive effect of diversity on a company’s bottom line, the McKinsey report being probably the most famous one, the Norwegian companies I have approached are very slow and reluctant in committing to the cause. We have individual ‘champions’ within companies who support our work and promote it internally and we’re very happy and grateful for this, but to secure a wider support is a hard and slow-progressing work.

Raising awareness of unconscious biases could be a good first step in negotiating a wider support. Recruiters and hiring managers have their unconscious biases just like everyone else, but in this case, these prevent them from interviewing candidates that could contribute greatly to the success of their respective companies. Becoming aware of one’s unconscious bias and actively addressing it can unlock a great pool of talent for many Norwegian companies.

“Your primary target group are trailing spouses. What type of discrimination do they face and how does their lack of opportunities affect Norway?“

The challenges of trailing spouses have a couple of dimensions. Firstly, most of them are women.

Even in a society as advanced as Norway, women still face discrimination in the labour market, in addition, the burden of the so called second shift (household, children) is mostly on their shoulders. Partners of non-Norwegians then often face the assumption that they would leave in a year or two, either to go back to their home country or to follow their partner onto another assignment.

What makes trailing spouses different from other immigrants (not refugees) is that they are in a country that is not entirely of their own choice. Surely, if they had to decide on an ideal location, they would not choose a place where they cannot work, where their skills, experience, and education is not valued, and where they are reduced to only home makers. At the same time, these people don’t need any special support, no upskilling or further education and no financial support from the state. In no way are they a liability, instead, they are most certainly a resource.

Meanwhile, highly educated people with successful high-profile careers in their home country are being told to take on jobs in cafes or shops to practice their Norwegian before they can get a job relevant to their level of education and experience.

In my view, Norway is missing out on utilising these resources in a time where people, knowledge, and innovation are becoming the main focus of the economy.

“How many in your network have been able to secure work in Norway as a direct and indirect impact of your work? Can you tell us a bit about the successful demographic? What is the ideal success for NFW in a few years?“

Social impact is hard to measure as there are so many external factors at play but we can say with certainty that three people got jobs as a direct impact of our work.

One of them secured employment through our informal cooperation with a big Norwegian company and the other two, as a result of job search workshops we organise – both contacted us afterwards and said the information about CV and interview presented at the workshop helped them in the job application and interview process.

There are two additional workshop alumni who secured employment and said they found the community or fellow expat job seekers helpful. Of course, there are many more who find jobs but either don’t let us know or don’t think our work contributed to it, because the impact of our work can be as small as them realising there’s nothing wrong with them personally and that the struggle they face is of a structural matter.

What is curious is that even though most trailing spouses that come to us are women, the majority of those that secure jobs (that I know of) are men – native English speakers I might add.

This shows us that there’s still a lot of work to be done in promoting true and equitable diversity.

The ideal success for NFW is a large network of companies contributing information and short term and/or project positions for NFW members. NFW has the potential to become a global organisation with the ever-increasing movement of skilled workers, but we need to prove the concept in Norway first.

“If you had the power to change the state of ‘affairs’ in Norway for Trailing Spouses and immigrants alike, what would you do? In other words, what specifically needs to change to further your cause?“

What Norway needs are meeting places. Professional meeting places where Norwegians can experience working with foreigners. Where all work towards the same goal and can meet each other in a context that allows them to leverage their skills and knowledge. Only this way can Norwegians find out that they have more to gain than lose, that they have something in common even if they can’t talk about skiing during lunch break, that a skill is a skill no matter if the skill-holder is called Stine or Papitha. When we figure out how these meeting places should look like and how to make them relevant for everybody involved, these will become a part of our strategy. And while everything seems impossible until it’s done, we are both optimistic and confident that we will do it.