I recently picked up a book on diversity at the bookstore and barely four chapters in, I have made several notes – mental and written – on thoughts to further explore. One of my basic constructs of diversity (as I understand it) is that while we are seemingly different, if we listened and empathized without judgment, preconceived notions and bias, that we are indeed, quite similar. Afterall, the genetic code or genome of every living human is 99.9% identical, thus only the left over 0.1% is responsible for our differences (i.e. skin color, eye color, hair texture).

It is common knowledge that diversity crosses common lines (i.e. race, ethnic, gender, sexual orientation, socio-economic status, age, physical abilities, religious beliefs, political beliefs, or other ideologies). Nonetheless, there are other factors that make us diverse that are not immediately visible.And as I continue to engage in conversations on integration and inclusion, I am learning that diversity also draws from various layers of our identity and emotional and perceptional disposition.So far, in spaces I have observed where these conversations occur, I have come to understand that diversity also arises from occupational interests and prospects, differences in skills and abilities (including how we perceive our innate skills and abilities), personality traits, values and attitudes. These as it turns out, also impacts on how we deal with the various baggage that life throws at us.

On dealing with baggage, many people endure experiences that might leave them feeling traumatized or depressed, either temporarily or permanently. Take people fleeing war torn countries, political, religious or social persecution, who have to leave almost everything and everyone they know behind to journey on to the unknown, not necessarily always for a better life, but for a safer one. Imagine trailing spouses or partners, who travel to new lands, leaving a respectable career, close friends, family, and the familiar as they venture into new horizons.

Think about youths who are survivors of atrocities, genocides, sexual assault, various forms of loss and have to deal in a new country, where other necessities await – learning a new language, securing an education or a job, integrating, making friends, and feeling like they belong in their new society. Now consider those who have had a relatively “easy and smooth sailing lives” (i.e. expats) who now have to contend with a daily “otherness” ascribed by society. And of course, there are those who we most often forget about in these conversations – those who are born, have grown up or continue to live in their country, but by some social and emotional construct, feel that they do not belong.

How do we empathize with others even when we may not remotely or fully understand their experiences? How can we curate safe spaces of sharing where people feel heard?

In a conversation I had a few weeks ago, I used the word, ‘trauma’ to describe an experience I had. In my view, it was traumatic. However, one of the people I was having the conversation with asserted that I should be careful about using the word ‘trauma’, he didn’t think my experience was traumatic, but he could see how it was difficult because I was mentally and emotionally weak. His comment left me puzzled and for a few minutes, silenced.

My brain ran rampant with thoughts: “had I read more into my experience (and pain) than I needed to? Was I emotionally weak because I allowed what he considered non-traumatic traumatize me? Had I overreacted to my difficult experience and could I have handled it better? Better still, could I have avoided my depression all together? This is what you get for sharing! Now you will forever be known as that weak girl”

And before I could slide deeper into my rabbit hole of doubt, I jolted myself back to reality. No! I did not overreact. I felt what I felt and did the best I could (at the time) to heal. I was not going to let this one slide. And although the conversation has moved on from my trauma and perceived mental and emotional weakness, I took it back, and spoke instead with an understanding he had not offered me, I tried empathy. I clarified that I can rationalize that his experience and privilege might not allow him to fully understand what I went through, and that was his prerogative. Nonetheless, it is not my reality. And while I welcome his opinion, I do not accept it as truth. And as such, his opinion does and will not silence my experience.

Who is to assign the intensity of damage each experience brings to each individual?

In the past couple of weeks, I have come to find that where conversations on diversity, inclusions, job opportunities, and mental health is concerned, many of us (including me) cannot help but compare our own situation to the experiences of others. This is certainly something we can unlearn.

Exhibit A: On Integration

Jane Doe: “I have found it extremely difficult to integrate into Norway. I have lost a lot of my confidence and barely have any friends. I feel alone here and do not have the space to freely express myself. I have been unable to find work, no matter how many applications sent in. I find the society closed off and this has worsened my depression. I was told that learning the language would help my situation, and I have a C2 (very high) level in spoken and written Norwegian, yet I have been unable to find a job. I am struggling.”

John Doe: “I have had a very good experience in Norway and things are really good for me here. The reason you feel bad is because in Norway people do not speak to you just because. So, you find it difficult to adapt. In Norway, people also have a great respect for personal space, and I think this is necessary, as opposed to countries where people are often presumptuous and impose on your space. So instead of sharing your feelings with people, Norway allows you to deal with yourself and introspect. In addition, the environment is so peaceful and the nature is stunning, so there are lots to do, even though you cannot find work. Moreover, the job situation is not unique to immigrants. Everyone struggles. You just need to be motivated enough. I found a great paying job that matched my skill after one year of job search and I do not even speak Norwegian.”

Exhibit A was inspired by a conversation I heard recently between two people. Both Jane and John arguably speak their truths, but John response could use a little bit of empathy. Perhaps it is human nature to often compare our situations with others and render feedback based on how we see the world. What we could do however is to try a bit of empathy in the process.

In addressing some of the points raised in Exhibit A, cultural codes and strong personal borders are not unique to Norway – they are also universal. Norway is a great country and often gets the stand-alone bad reputation for being ‘cold’, nevertheless, many European countries (and particularly, Germanic ones) appear to be ‘cold’ from an openness parameter. Where employment opportunities are concerned, it may be easier for those with specialized expertise to secure work. For example, it could be easier for people to find work in an oil rig if they have the required skillset and certifications, or an Accountant with a CPA license to find work in an audit firm, as opposed to someone with only an accounting degree. Resultantly, their invitation to an interview or ability to secure work might inform on their wellbeing.

Moreover, I think it is a generalised opinion to believe that people from other countries find it difficult to deal with themselves and introspect – in some ways, depression arises because people’s feelings are repressed and as such, their inability to fully feel and express themselves contribute to their depression – and this is why therapy helps. Finding a safe and judgment free space to share, vent, cry and heal matters. Depression is indeed universal and can happen to anyone, in any country. What is important is that people have an avenue or outlet to share and connect with whatever forces that allows them to heal.

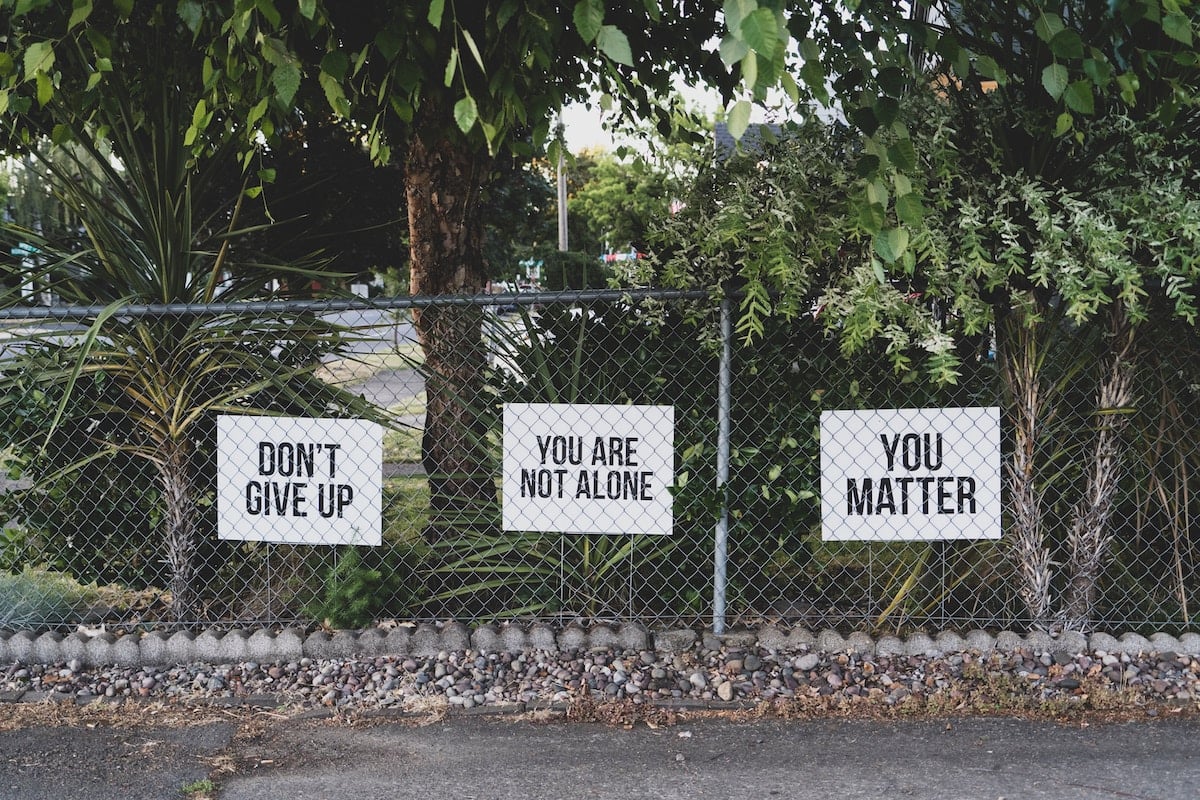

Practising empathy requires our creation of judgement free spaces so people feel empowered to share. Safe spaces do not only have to be in private homes or venues, but can also be in public spaces, buses or in walking down the street with a friend.

What I am trying to say here is that YOU can be a safe space.

And creating a safe space is not about comparing experiences. We do not need to have an answer, advise or a solution. Sometimes, we only need to listen.

The fact remains that it is difficult and sometimes even scary to start afresh in anything, especially when you are leaving something (perceived) better or comfortable behind. That our ability to thrive – that John’s ability to live what he perceives to be a good life in Norway, does not have to come at the expense of Jane living hers, and vice versa. As we are all individuals, we can experience the same environment and situation differently. This of course has a lot to do with our personalities, where we are coming from, and the value we place on things which matter to us.

I am of the opinion that all of our diverse wellbeing can co-exist – that’s the beauty of diversity and inclusion. The goal is to have a society where everyone feels their version of happiness and has a good life. Perhaps, in our world today, the idea of collective wellbeing is a utopia. Nonetheless, I believe that everyone does better when they feel heard and/or understood. And we are all worthy of being heard.

So, in conclusion, in order to create safe and judgement free spaces, empathy is the way.